First things first: What's Linux, anyway?

Glad you’re back! Today, let’s tackle a fundamental but super-important question:

What exactly is Linux?

Knowing this is your ticket to figuring out why your Linux-based systems behave the way they do.

Getting your head around the Linux core components is the key to understanding how your systems really tick.

It All Starts With the Kernel

If we want to break down Linux to its purest form, we need to talk about the Linux kernel - the thing Linus Torvalds created himself back in the days.

Most of the time, when someone says “Linux,” they’re talking about the entire OS, but strictly speaking, Linux is just the kernel, the very heart of the system.

Want a nostalgia trip? Head over to kernel.org, and you can dig through code archives going all the way back to version 1.0, published in 1994, with a compressed source size of 1 MB.

Try to find the file linux-1.0.tar.gz at https://www.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/.

Sure, Linus released the first kernel back in 1991, but it was version 1.0 that hit the “stable” milestone.

Fast-forward to now, and we’re dealing with kernel version 6.16 from July 2025, weighing in at about 236 MB compressed. That’s one heck of a jump! Why the massive growth? Well, mostly because of device drivers.

What’s the Kernel Actually Doing All Day?

Here’s a quick rundown of the kernel’s main jobs:

1. Hardware Abstraction

The kernel creates a handy hardware abstraction layer.

You’ve probably heard the saying, “Everything is a file.” Well, on Linux it’s not exactly everything - but close enough: Most hardware devices are accessed through special files, the so called device files.

Let’s take /dev/nvme0n1, for example. On my system that’s the first NVMe hard disk. On your system, disks can have different names, like for instance /dev/sda.

And you can interact with these files just like with any other file (though careful there!).

If you give your disks name as a parameter to cat like here:

sudo cat /dev/nvme0n1

you’ll see a bunch of unreadable gibberish - raw bytes straight from your disk - but the cool part is how Linux lets you use familiar tools to interact with hardware.

2. Process and Resource Management

Linux is built to multitask like a boss. And it’s the kernel’s job to juggle all these running processes, share CPU time, and allocate memory resources.

Just run top, and you get a live snapshot of how the kernel is orchestrating the show, smoothly juggling all the processes across your CPU cores.

3. Security and Isolation

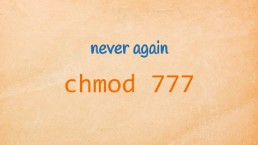

Keeping things secure is another big kernel responsibility. It manages permissions and isolation between different users and processes.

Ever tried this as a non root user?

cat /etc/shadow

# → Permission denied

That’s the kernel stepping in, preventing normal users from accessing sensitive data and keeping your system secure.

4. Device Drivers: The Kernel’s Big Chunk

A massive portion of kernel code belongs to device drivers, those “tiny” code bundles that enable your hardware to talk with Linux. From network cards to webcams, drivers are crucial.

Unlike Windows, where you’d often install vendor-provided driver packages, Linux drivers usually come built into the kernel. Installing a new driver usually means upgrading the kernel - either with regular patches and updates or via a complete distribution upgrade.

Sidenote: There are also solutions like DKMS (Dynamic Kernel Module Support) to update drivers independently.

5. Kernel Modules: Keeping Things Modular

If you check out the kernel image your system loads at boot time (on my system for instance this is /boot/vmlinuz-5.10.230), than you’ll see a relatively compact image. On my system here it’s about 9.7 MB.

Well - that’s the code that’s just enough to bring up your system into a minimal working state.

Everything else that’s needed? Can be loaded at runtime:

Since kernel version 2.0, Linux has used modular kernel components - called kernel modules. They’re stored here:

/lib/modules/<kernel-version>/

Wanna see what modules you’ve got? Just run something like:

find /lib/modules/5.10.230/ -name '*.ko'

(don’t forget to replace the number with the version number of your kernel, uname -r helps you with this)

On a typical system, you might have hundreds of these modules, covering everything from networking protocols to hardware support.

On my system, I see:

- 983 kernel modules (the `.ko` files)

- Totaling over 100 MB of compiled binary code

(I estimated this withdu -sh /lib/modules/5.10.230/)

6. Networking

The Linux kernel handles networking too - entirely within kernel space. Pinging a system, establishing TCP connections, packet routing, firewalls - the entire network stack is kernel-managed.

So, Is the Kernel an Operating System?

Technically speaking, no. The Linux kernel alone doesn’t make your computer usable.

To actually use it, you need:

- A shell (like

bash) - Command-line tools (

cp,ls,cat, etc.)

That’s where the GNU Project comes in.

GNU Project: Finishing the Puzzle

The GNU Project, launched by Richard Stallman back in the ’80s, aimed to create a free, Unix-compatible OS.

While their own kernel (Hurd) wasn’t ready at the time Linux was created, their toolkit was. So once Linus’ kernel appeared, it was combined with these GNU tools, creating what we now call GNU/Linux.

These GNU tools include:

- Bash – your command-line interpreter

- Core utilities – basic commands like

ls,cp,mv, andcat - Advanced tools – handy commands like

find,grep, andtar - Compilers – like gcc for compiling code

And because these tools are re-implementations of classic Unix commands, working on a Linux system feels right at home if you’ve used other Unix-like systems like macOS or Solaris before.

Here is what to do next

If you followed me through this article, you certainly have realized that knowing some internals about how things are working at the Linux command line, can save you a lot of time and frustration.

And sometimes it’s just fun to leverage these powerful mechanics.

If you wanna know more about such “internal mechanisms” of the Linux command line - written especially for Linux beginners

have a look at “The Linux Beginners Framework”

In this framework I guide you through 5 simple steps to feel comfortable at the Linux command line.

This framework comes as a free pdf and you can get it here.

Wanna take an unfair advantage?

If it comes to working on the Linux command line - at the end of the day it is always about knowing the right tool for the right task.

And it is about knowing the tools that are most certainly available on the Linux system you are currently on.

To give you all the tools for your day-to-day work at the Linux command line, I have created “The ShellToolbox”.

This book gives you everything

- from the very basic commands, through

- everything you need for working with files and filesystems,

- managing processes,

- managing users and permissions, through

- software management,

- hardware analyses and

- simple shell-scripting to the tools you need for

- doing simple “networking stuff”.

Everything in one single, easy to read book. With explanations and example calls for illustration.

If you are interested, go to shelltoolbox.com and have a look (as long as it is available).